Armenian News Network /

Groong

CHRISTMAS CELEBRATION

FOR ARMENIAN ORPHANS IN Mezreh (KHARPERT) JANUARY 8TH, 1920: FROM

LETTERS AND PHOTOGRAPHS1

(Superscripts refer to Endnotes which will be

found at the end of our text. Two Appendices, one on dates for

Christmas and another on Kharpert follow the Endnotes.)

Armenian

News Network / Groong

January 6, 2014

Special to Groong

by Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor

Long Island, NY

Kristos dznav yev haydnetzav

Orhnyal e haydnutyunn Krisdosi

Dzezi, mezi medz avedis

Քրիստոս ծնաւ եւ յայտնեցաւ

Օրհնեալ է յայտնութիւնն Քրիստոսի

Ձեզի, մեզի մեծ աւետիս

Christ is Born and Revealed Amongst Us!

Blessed is the Revelation of Christ!

Good tidings to you and to us!

ABSTRACT

AND COMMENTARY

The Armistice of

Mudros was signed on the Greek Island of Lemnos on October 30,

1918. With this signing the Turks agreed to bring to an end on

November 1 the hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the

Allies. The Armistice of November 11, 1918 between Germany and the

Allies ended World War I in Europe. Well before all this and

certainly afterwards, a tattered, pathetic remnant of the Armenian population

who had avoided or survived attempts by the Turks to annihilate and exterminate

them showed their faces in earnest and flocked to a few places like the

Kharpert (Harpoot) region. They were for the most part young, indeed

most were children − and most were full orphans. There were

even some ‘oldsters’− mainly women but very occasionally, a feeble old man. The

chapter concerning what comprises their “stories” has yet to be dealt with in

full detail. Quite a few accounts do, of course, exist in the form

of written and oral history memoirs by survivors (usually in Armenian). But

it is all too often assumed that most know about organizations like the Near

East Relief In fact, this organization came into being largely to

help these orphan survivors. It is part of American history that is

poorly known − even unknown. The “Story of Near

East Relief” written by Rev. Dr. James Levi Barton, the man who was a major

factor in its founding and operation is relatively well known. He

guided its activities for nearly all of the 15 years it

existed. Many consider Barton’s book to be the definitive

history of that organization. We agree that this is appropriate and

justifiable. It also happens to be the only substantial story

written. Even so, Rev. Barton titled his book “Story of Near East

Relief, An Interpretation” (our emphasis). He did not

say, as some have erroneously claimed, The History. We

believe that a considerably more humanized and personalized story of Near East

Relief can be and needs to be written. The Christmas celebration at

Mezreh/Harpoot on January 8 [no, not the 6th] 1920 for Armenian orphans that will

be described here is but one event that goes far to put a more personal face on

the story of the recovery and rehabilitation of the Armenians from near total

destruction. True, the full story of the Armenians of Kharpert and

elsewhere is, of course, one of much sadness and disappointment, but the fact

that this celebration took place in a very significant region of historic

western Armenia, the name of which is well-known to many Armenians in today’s

Diaspora, and at a time when one was not at all not sure as to who had managed

somehow or other to live or to become ‘free or liberated’ as some of the

survivors would say in Armenian “inchbess azadetsak” deserves to be

told. We are happy to be able to do this in a very small way based

on archival materials, and even to illustrate the ‘festivities’ with a few

period photographs. Readers all know and all those relief workers on

site knew that January 6th is ‘Armenian Christmas’ – but

as it turned out it was on January 8 that this particular celebration took

place.

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary

accounts, especially those written by non-Armenians, of what happened in

Post-World War I Turkey and elsewhere repeatedly emphasize that no other nation

suffered to the same extent as the Armenian nation. The Mudros

Armistice which ended hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies was

signed on 30 October 1918. Paragraph 24 included the following proviso making

clear that “In case of disorder in the six Armenian Vilayets the Allies reserve

the right to occupy any of them.”

News spread

quickly that Turkey had lost the war, and “deportees” such as those who could

and wanted to return would end up being allowed to go back to their ancestral

homes. Some survivors of the horrors of the deportations made

attempts to seek safety among those who could protect them, and even attempted

to return to their home villages (naively thinking they might still be like the

one they knew when they were forced to leave, or that they could locate family

members or friends “back home.”) They came not only from

very close-by places or relatively close-by areas, but even from far-away

regions like the deserts of Der Zor and south of Mosul etc. In the

words of some survivors known to us who recounted the events of the period said

“I went back to find my Mother. What else could I do? − ‘Yehd

gatzee…”

The main purpose

of this paper is to provide some details of a Christmas celebration

arranged for Armenian orphans by the American relief workers at

Mezreh right after the war. (Incidentally, the word orphan is used

in the broadest sense of the word. This will become clear as we

proceed.) It is surely a miracle that any Christmas could be

celebrated, much less one in this remote region so soon after the

genocidal events had taken place.

The celebration

seems deliberately not to have focused on the religious aspects of the holiday

even though many of those who planned and carried out the celebrations were

deeply religious individuals. Some had even served as missionaries

as recently as a couple of years earlier. This Christmas celebration

was tailor-made so to say for the Armenian youngsters and their immediate care

givers−their Mairigs and Kuirigs (the

‘mothers’ and ‘sisters’ who supervised and looked after these

orphans on a daily basis). Clearly, the Christmas events were

possible only because a group of American relief workers were on the

scene. These dedicated volunteers made certain that at least some

relief resources, scarce as they were, would be used in trying to do something

on Christmas for all those in their care who had suffered so

greatly. The relief workers had been allowed into the Kharpert area

only by mid-June 1919, around 6 months after the armistices had gone into effect. They

had hoped to be able to pitch in much earlier and help those in need that they

had been told about back home but it had been deemed unsafe by those in charge

to travel into the remote interior of Turkey until then.

The

Kharpert (Harpoot) Region2

The early

American Protestant missionaries to the Kharpert region knew that the

pronunciation of the place-name started with a guttural H (for Kh) Har-poot and

said so in print more than once.3 The spelling in English

with an ‘H’ was, of course retained thereafter but the early reminder in print

that it was to be pronounced with the guttural seems to have been

lost. Many do find it a challenge to make guttural

sounds. (Appendix 2 devotes a fair amount of space to the region.)

Mise

en ScŹne

Before we delve

into the main body of our presentation on the “Christmas for Armenian orphans”,

it will be useful to present what is often called a mise en scŹne,

or a description of the physical setting of the action.

Many

readers of Groong will know that Kharpert was not only where their ancestors

and relatives came from in the Old Country, but also that it was the center of

a busy field of American Protestant missionary activity – carried on

largely by Congregationalists. The ‘parish’ field was huge by the

standards of the day, and even today one marvels at the territory they chose to

cover. It took two weeks’ journey to traverse by horse from north to

south, and a full week east to west.

For a

succinct perspective of Harpoot in the late 1800s one can do no better than to

quote an early account by Rev. Dr. Herman N. Barnum from his “Sketch of the

Harpoot Station, Eastern Turkey” published in The Missionary

Herald vol. 88, April 1892 pgs. 144-147).

“The

city of Harpoot has a population of perhaps 20,000, and it is located a few

miles east of the river Euphrates, near latitude thirty-nine, and east from

Greenwich about thirty-nine degrees. It is on a mountain facing

south, with a populous plain 1,200 feet below it. The Taurus

Mountains lie beyond the plain, twelve miles away. The Anti-Taurus

range lies some forty miles to the north in full view from the ridge just back

of the city. The surrounding population are mostly farmers, and they

all live in villages. No city in Turkey is the center of so many

Armenian villages, and the most of them are large. Nearly thirty can

be counted from different parts of the city. This makes Harpoot a

most favorable missionary center. Fifteen out-stations lie within

ten miles of the city. The Arabkir field, on the west, was joined to

Harpoot in 1865, and the following year…the larger part of the Diarbekir field

on the south; so that now the limits of the Harpoot station embrace a district

nearly one third as large as new England.”4

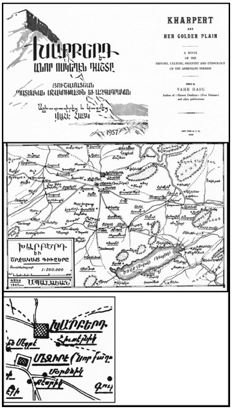

Map

of the Region

There are a fair

number of contemporary maps of the Kharpert-Mezreh area but very few that we

are aware of which are detailed enough to give the names of very many of the

smaller, or even larger villages in the region. These are names that

one often hears about through accounts of Armenian immigrants who ultimately

made new lives for themselves in America, initially in New England, and then

later in California and elsewhere. The line-drawing map we have

selected (Fig. 1a and an enlarged area in Fig. 1b) is by no means perfect or even

complete but it does give a good idea of the immediate area that we are

concerned with for our “Christmas for Armenian orphans.”

Figs.1a and Fig.

1b. Map reproduced from “Ten Years on the Euphrates; or primitive

missionary policy illustrated” by Rev. C.H. Wheeler, American Tract Society,

Boston, 1868). Original foldout map facing pg. 38. The

precise location and relative positions of the places named is imperfect but

the map serves our purpose here very well.

The great British

statesman Winston S. Churchill described what happened to the Armenians in the

course of World War I and the virtual emptying out of their ancestral homeland

of their presence in the following way. “In 1915 the Turkish

government began and ruthlessly carried out the infamous general massacre and

deportation of the Armenians in Asia Minor…the clearance of the race from Asia

Minor was as complete as such an act, on a scale so great, could well be…There

is no reasonable doubt that this crime was planned and executed for political

reasons…”5

In the final

report dated February 9, 1918, United States Consul Leslie A. Davis presented

to the State Department’s Consular Service a 132 page document in which he

described in considerable detail the events associated with the massacres and

the deportations as they unfolded and happened in his Harput Consular

district. He described not only what happened in Harput and Mezreh

during those fateful years but told of what he encountered in a number of

nearby villages as well.

“The Mohammedans

in their fanaticism seemed determined not only to exterminate the Christian

population but to remove all traces of their religion and even to destroy the

products of civilization. It was a sad sight to see all this ruin

and destruction as I rode through these deserted villages during the following

year and a half and saw empty homes, from so many of which husbands and sons

had gone to America where they were now ignorant of the fate of their

families. Among the villages I visited were Huseinik, Morenik,

Harput Serai, Upper Mezereh, Kesserik, Yegheki, Sursury, Sursury Monastery,

Tadem, Hooyloo, Shentelle, Garmeri, Keghvenk, Kayloo, Vartatil, Perchendj,

Yertmenik, Morey, Komk, Hoghe, Haboosi, Hintzzor, Dzaroug, Harsek and

Pertag. It would be tedious to describe each one in detail, for the

scenes in all of them were similar. I visited most of them many

times and received inquiries about thousands of their inhabitants through the

Department and the Embassy”6

Where

Did the Armenian Orphans Come From? How Did they Get There?

In view of what

we have written above, and to allow us to proceed with a proper understanding

of the situation, we need to address a couple of very important points.

“Where did these

orphans and genocide survivors come from?” How was it possible to

celebrate Christmas in January 1920 in a region that had been for all practical

purposes emptied of people through mass murder and massacre, violent uprooting,

deportation – by “genocide” to use the word devised by Raphael Lemkin, a word

which he freely used to describe the Armenian experience?7

We should start

by stating that the murders, deportations and forced exiles during the summer

of 1915 onwards from all the regions inhabited by Armenians were by no means

always complete or necessarily thorough. Kharpert was one of those

areas in which initially at least, the heinous ‘job’ was not complete despite

the many atrocities and crimes against humanity that were generally executed

with a studied cruelty that had not been seen in centuries.8

Some of those who

seek to deny the reality of the genocide of the Armenians by the Young Turk

government have repeatedly drawn attention to the fact that Armenians could be

found in the region when the Armistice with the Allies was signed at

Mudros. In other words, Armenians could not have been killed through

any genocide or massacre or any other kind of criminal action (hence

the expressions ‘so-called massacres or so-called genocide’). This

patently wrong view that virtually all Armenians had to have been eliminated

reflects the level of ignorance of those who have very little understanding of

what the legal, not to say moral parameters of the crime of genocide is all

about. Perhaps deniers and those who seek to misrepresent the events

of 1915 and onwards clutch at any and all straws to defend their ill-guided

position?

In the same vein

it is worthwhile emphasizing that nowadays there are too many people who seem

to view genocide from the highly distorted perspective that this “crime of

crimes” should be derived from − imagined and pictured if

you will − the fastidiously organized genocidal operations of Nazi

Germany against Jews and other undesirables like gypsies, Slavs, Jehovah’s

Witnesses, homosexuals etc. ̶ (one does not even

have to read about the Holocaust. One can very easily and

conveniently see events associated with it on T.V., at

the movies, on YouTube and so on. Some have even sarcastically

opined that a virtual ‘Holocaust industry’ has emerged.)

But the outback

regions of the Ottoman Empire from which the Armenian orphans that we are

concerned with here, and who attended the Christmas celebrations of late

1919-1920 cannot be compared in any general way with Europe. The

regions of historic western Armenia were certainly not continental Europe, be

it Germany, Austria, Poland or elsewhere. Succinctly stated, Turks

did not have the organizational skills of Nazi Germans. Certainly

Turkey as a whole was not Europe. Even so, it has been noted by more

than a few of those who believed that they understood the Turks and ‘knew’

their usual modus operandi that the Turks seemed surprisingly

organized when it came to dealing with the Armenians in the course of the

genocide.9

A considerably

more accurate rendition as it relates to Kharpert City, Mezreh and the villages

in the environs is that the deportations were done by what some have referred

to as ą la Turque, that is in stages, fits and spurts,

inconsistently and erratically. [Accounts of the emptying of the

villages − inchbess aksorvetsak, in Armenian “how we were

exiled” – those villages and hamlets whose inhabitants were exclusively

Armenian show that forced ejection was done much more readily than those that

had greater or lesser populations intermixed with Muslims − all of that

is another story but the reader will get the idea].10

According to Dr.

Ruth A. Parmelee11 who was on site in Harpoot some Armenians

simply “escaped from the exile or deportation columns, usually because they

were able to bribe their guards. But those who had not been able to

save any of their money were obliged to stay with their company later to be

pushed on, probably to some slaughtering ground, there to be disposed of.”12

We will present

here some excerpts from notes that Dr. Parmelee used for a talk she gave in Virginia

in September 1917. This was of course after getting back to America

after she and other Americans left Turkey with Consul Leslie A. Davis when the

Turks and the United States severed relations on April 23, 1917. Dr. Parmelee

wrote:-“Although our province was a slaughter-house for thousands of exiles

brought from different regions to the north of us, a number of people from

these convoys escaped and remained in or near the city

[Harpoot]. Then, although thousands were deported from our province

to suffer unspeakable things in their wanderings towards the south, yet several

thousands in the villages round about, succeeded in hiding when the deportation

was decreed. After the immediate danger of being exiled seemed past,

many of these refugees flocked to the city of Harpoot without food, clothing,

or household utensils. Immediate relief was needed. For a

year and a half before we left, our circle was occupied in providing bread,

clothing and work, if possible, for these women and children; fighting the

diseases resulting from filth and lack of nourishment; running a primary school

for several hundred orphans and a boarding-school for nearly a hundred homeless

girls; and using all these forms of work as a means of spiritual influence.”

What we have just

said, of course, applies in the main to females who had by one means or other

avoided ‘full deportation’ so to speak. So far as grown men (martikuh)

or adolescent males (dughakneruh) were concerned, occasionally special

reprieve, usually temporary, was given to a few of those who were in what might

be called ‘critical industries’ or at least critical for some at a specific

time or other. Some bakers (again known to us through personal

stories) who, for instance, could bake bread for the Turkish military were

allowed to stay and work their ovens. Tailors who owned and could

use sewing machines were sometimes retained to sew military uniforms, and even

garments for the wives and families of Turkish officers etc. The

same applied to shoe makers who could make boots for the military

etc. Makers of kerosene and oil lamps and lanterns (labders in

Kharpertsi Armenian) were exempted for a while, and on and on and on, so forth

and so on. We will not include stories of the odd Armenian males or

youths who feigned death, or those who were taken for dead as they lay hidden,

covered in piles of those slaughtered, or even women left for dead who crawled

out of wells over dead bodies, eventually to escape (yet again known to us from

survivors). Some of the men and youth who survived massacre were

sometimes dressed as women, and were spirited as quickly as possible out of the

region by Kizilbash Kurds through the Dersim and eventually towards

Russia.

When all is said

and done, each of these groups of Armenians, totaled a relatively small number,

and then again, many were eventually deported and/or killed, even those who had

nominally gone through the motions of converting to Islam. It often

took more than circumcision and taking a Turkish name to convince the Turks of

the sincerity of the conversion of any Armenian man. These converts

were usually used for whatever purposes and eventually usually dispensed

with. Surely not all though, because we are starting to learn of

many converted Armenians (albeit mainly women) who had married Turks, had

offspring and whose descendants are now ‘surfacing’ in a nominally more

liberalized Turkey. Turks who have oftentimes fantasized about the

purity of their ‘blood’ will have a lot of contemplating and reckoning to do

when they finally acknowledge that they frequently have more than a

small dose of Armenian genes in them.

Dr. Parmelee

wrote quite frequently in her correspondence back to America about the

situation that relief workers had to confront when they reached Harpoot in

mid-June 1919 and we thus have a fair amount of detailed information

available. She was very familiar with the area and knew the Armenian

language as a result of having been born of missionary parents in Trebizond. She

had served at the Harpoot station at the Annie Tracy Riggs Hospital, known

commonly as the “American Hospital” from 1913 until 1917 when the Americans had

to leave Turkey. She wrote in 1919:-“As soon as Armenian women

and children serving in Turkish homes heard that the Americans were receiving

orphans, many of them ran away from their masters and flocked to

us. On admission, these newcomers were housed in a detention home

until they had their first bath and their medical examination. From

the start, the medical department had its hands full, what with the eye

diseases, the different kinds of sores, all the cases of

malnutrition. In fact, some of the children had been put out by

their masters, because they were in such bad physical condition as to be of no

more use to them. One such girl

was dropped in the hospital corridor one day, her fractured leg of a week’s

standing incapacitating her for further service to her Turkish

master. After recovery, little Loosig [little Lucy] became one of

our faithful hospital maids. I remember overhearing one little

fellow with thin body and grayish complexion say on the street to an urchin a

shade worse than himself, “You must go to the hospital, you will die if you

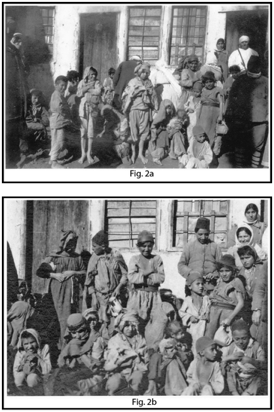

don’t.”12 (See Figs. 2 a and b for photos of a few of these new

inmates outside side the scrub station.)

Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b. Scene outside the scrub station for Armenian orphans. (See excerpt from Dr. Parmelee’s letter above.) In Fig. 2a Margaret H. Niles is on the far right. The condition of the orphans was deplorable of course but one somehow can detect a bit of relief in some of their faces knowing that they would be taken in, and thus be ‘saved.’ Many others waited for long periods patiently hoping to get in but could not be admitted because there was insufficient room and money to cover costs for the support and maintenance of all who needed it. The upper panel (Fig. 2a) is from the collection of Frances and Laurence H. MacDaniels’ Near East Relief Album at Oberlin College Archives. The lower shot (Fig. 2b) is from a private collection.

Readers will not

be surprised to hear that there are extensive archival materials in the U.S.A.

and elsewhere associated with the relief given by various organizations. Most

of these have barely had their surfaces scratched. The “Near East

Relief” materials comprise one of the most significant of these

archives. It came into being largely because the Red Cross had its

hands full. The Red Cross people (other than Clara Barton’s mission

to Turkey after the Hamidian massacres) had little familiarity with the region

unlike the many American missionaries who had served in the region before the

war (more below). But there were others of course.

Many have heard

of the Near East Foundation Archives housed at the Rockefeller Archives at

Sleepy Hollow, New York but having suffered loss through fire and de-accession

they seem to us to have fewer items dealing with the earliest relief efforts,

in contrast to a richer collection of the later ones (Personal knowledge).

Volunteers,

mostly Americans but some other nationalities as well, especially the Danes at

Mezreh, attempted to save and extend some friendship to the remnants of the

Armenian people surviving the slaughters and hardships, especially the orphans

both in Turkish Armenia and in Russian Armenia. At Harpoot, and

everywhere else, the bedraggled Armenian remnants were all inevitably exhausted

and infected with every sort of disease imaginable –many were described

as “half-dying”.

Mary W. Riggs,

the sister of Rev. Henry Harrison Riggs, who like Ruth Parmelee was from an old

missionary family and spoke Armenian, had returned to Harpoot with the first

returning American relief workers in June 1919 summarized it this way:-“After

the terrible days of open massacre and deportation were over there came a time

when by tens, and then by hundreds, the groups of ragged homeless refugees

began to appear in Harpoot – exiles from the north or natives from the

place returning after months of wandering to ruined homes. All in

utter want and deadly fear – two-thirds of them children – the rest

women – few men survived. For years an American mission,

centering about Euphrates College, had worked in old Harpoot. It

proved a very friend in need and relief sent from America saved thousands

alive [in contrast to saving departed souls]. Even after

the Americans were forced to leave work went on in the hands of one faithful

woman [really two who were Danish subjects] – Miss [Maria] Jacobsen [and

Miss Karen Marie Petersen] struggling to keep alive the little children who had

been rescued and placed with destitute Armenian women. The Harpoot

Unit now includes thirty-four American workers, of these, seventeen are now

located in the City of Harpoot, eleven in Mezereh, three in Arabkir and three

in Malatia…. “We keep taking in new orphans, mostly little boys

who have run away from their Turkish masters. We average forty new

children a week. At the same time we are giving back to their mothers

and other relatives those who were taken in during the summer or last winter

[1919] when their relatives were not able to keep them. An allowance

of money is made, when necessary, so that they may not suffer too

much. It is a sad business at best, putting the children out, for in

most cases they are better off with us than with their

relatives. There are many tears shed, and my heart aches as I send

them out. But our funds do not permit us to take care of them longer

in the orphanage.” (From a report entitled “Harpoot” by Mary W.

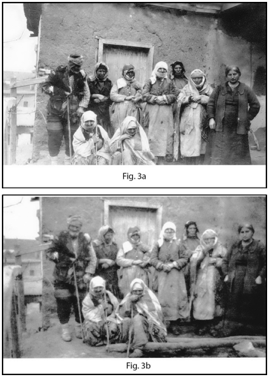

Riggs in the New Near East May, 1920.) See Figs 3 a

and 3b for photographs of some of the considerably older survivors.

Figs. 3a and

3b. Pictures of some of the adults who survived in

Harpoot and were helped by the Americans. The Armenian woman on the

far right still remains unidentified but she is what may today be termed a

“caregiver.” Fig. 3a derives from the MacDaniels collection at

Oberlin College Archives. Fig. 3b derives from Smith College

Archives. We have seen still another photograph of this group,

slightly different shot, in a private collection. Again, multiple

exact prints or near-exact prints serve to underscore that photos were often

shared and exchanged between and among relief workers. The negative

for Fig. 3a exists and was taken by Dr. L.H. MacDaniels (more later).

American

Committee for Relief in the Near East – the A.C.R.N.E.

We have not made,

nor will we make, any special distinction in this paper of what came to be

incorporated as the Near East Relief [N.E.R.], and its predecessor

organizations such as Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, American

Committee for Relief in the Near East [A.C.R.N.E.], and ultimately Near East

Relief. It will be understood that the various names of Near East

Relief over time merely reflects the ever-evolving emergency that confronted

those who took on the unprecedented challenge of saving lives, offering relief

and rebuilding lives for hundreds of thousands of victims. One

cannot overstate the role played by Near East Relief in ‘saving’ the Armenians

of the Near East. The Armenian nation was at the very lowest point

in its long and oftentimes sad history as a result of the Genocide.13

Photographs

from the period relating to Harpoot

Photographs associated

with orphans, and even seniors who survived the genocide against the Armenians

by the Young Turks from 1915 to 1923 understandably deal largely with their

sufferings. Virtually all these pictures focus on the great need for

help, both financial and otherwise, from donors. They fall into the

category of Publicity Photographs. Many, indeed most, images

provided to the public in magazines and in newspapers may justifiably be

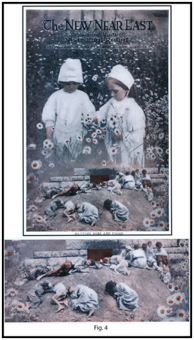

described as pathetic (see Fig. 4 for a picture from the cover of New

Near East May 1920, the very issue in which the report by Mary W.

Riggs written from Harpoot and quoted above is to be found). One has

to look very hard to find anything that even remotely approaches what might be

regarded as ‘cheerful.’ A considerably less investigated, and hence

underexploited source of photographs come from albums and collections assembled

to greater or lesser extent by relief workers and relief workers who had served

earlier in a missionary capacity – we might add “mainly”, but by no means

exclusively.

And, it needs to

be underscored as well that the vast majority of photographs, publicity and

otherwise, derive from those more formal photographs by professional

photographers and snapshots by amateurs taken on site or during service in

Armenia, specifically from the Erivan, Etchmiadzin and Alexandropol

regions. There indeed was immense suffering and hence great need in

these places, but such locations were where the relief workers and care givers

would be able to remain considerably longer than those workers who would be allowed

to remain in Turkey. Many will be familiar with photographs taken in

connection with the huge orphanages –some accommodating 17,000 or so

orphans and one said to be the largest orphanage for anyone,

anywhere in the world.

For all these and

other reasons relatively few photographs derive from the regions of historic

western Armenia (the six Vilayets) where Armenians had been concentrated in

Asiatic Turkey. (It is all the more ironic that there are relatively

few photographs since Armenians were the prime photographers of the

Empire.) The explanation for this state of affairs is simple of

course −the region had been emptied and devastated through the genocide

ordered by the leaders of the Central Committee of the Young

Turks. Some Armenians sought refuge in Russia, especially those who

came from Vilayets that were relatively close to the Caucasus. The

fact that there are a substantial number of people in Armenia today who have

roots in Van is yet another matter – many followed the Russians in

retreat.14

Fig.

4. Cover from the May 1920 issue of The New Near East (volume

5, number 9) seeking to elicit pity and sympathy from potential donors to aid

in relief work. The upper portion of the colorized image shows

youngsters in America plucking daisies in springtime. By way of

contrast, starving Armenian children lie in squalor and dire

need. The lower part of the cover has been enlarged to allow a

closer look. The colorized cover derived from a black and white

photograph which will be recognized by some.

Christmas for Harpoot Orphans

On very rare

occasion one comes across stories of situations which seem to have offered a

bit of a break, if only a seemingly insignificant or temporary one, from the

normally difficult daily tribulations that most Armenians

endured. Some of these sporadic events can even be regarded as

heart-warming. This is why we have chosen to focus on one of the

very few ‘happy’ occasions known to us. It deals with a Christmas

for Armenian orphans at Mezreh, January 8, 1920. January 6th is, of

course the exact date for Armenian Christmas but the 8th was

selected for convenience. Missionaries serving among Armenians often

wrote home gleefully that they had three opportunities to celebrate Christmas

− December 25th, January 6th and January 19th! (See

Appendix 1 for some details.)

The

Christmas Celebrations

Our plan for this

paper is first to present a published account deriving from a report that was

written by Rev. Dr. Henry H. Riggs (called Harry by family and close friends)

and sent to the English-language publication named The Orient in

Constantinople. The Orient was widely read by

missionaries and others and was put out by Bible House (printed incidentally

weekly by Armenian printers) but Riggs’ communication did not appear in print

until late March 1920! (Publication of The Orient had

ceased at the end of 1915 when the vast majority of missionaries had already

left Turkey.) We have retyped the notice which appeared in the March

24th 1920 issue [volume VII no. 17 pg.

163]. H.H. Riggs’ account will then be built upon to provide some

greater detail by using excerpts from contemporary letters and

accounts. We believe that this approach will reveal some more of the

human element in it all. Clearly Dr. Riggs was uplifted by the

occasion. We hope that all this will also show how a relatively

short report can be, with a little bit of luck, made more complete, and take on

an additional human face.15

“NEAR

EAST RELIEF SECTION”

“Christmas for the Harpoot Orphans”

(A delayed letter

dated January 13th gives such a vivid picture of the happiness

of the orphan children celebrating Christmas, that we reproduce a part of it

despite the fact that Christmas seems a long way back.)

“I

wish you might all have seen the wonderful sight that I saw last Thursday [8

January], when we got all our orphanages together for a Christmas

celebration. It thrilled me through and through and gave me

inspiration for the work of the new year.

It

was a glorious day with bright sunshine and no snow on the ground, the last of

quite a succession of such days, and everyone was happy and

excited. At noon they started towards the hospital yard where they

were to meet, each orphanage sending out its 75 to 100 children with two or

three workers, and from our house on the hill we could watch these little

groups winding down towards the plain. It is a distance of three

miles, and as there were many little tots to go, their progress was slow. The

tiniest ones rode on the backs of the older boys and girls.

The

hospital yard was ready for them. In the center was the pretty tree,

and all about were signposts bearing the numbers of the orphanages, −1 to

30, omitting only three numbers, because the Old ladies Home, the Scabies

hospital and the Infirmary on the hill could not be represented. As

each orphanage reached the gate, the children formed in line and marched to the

post bearing its number and grouped around the post. Many sat on the

dry ground, some had blankets under them, and many stood up. At last

our 2,500 orphans and several hundred others, − workers, hospital

patients and friends, − were all placed and I had the privilege of

standing on the hospital steps to call off the numbers of the

program. From that spot I could see every one and enjoy their joy.

While

people were still getting arranged, Mr. [Gardiner] Means went about from group

to group and gave them lots of fun. He had them shout out the

numbers of their orphanages, counting from 1 up in unison. It helped

to keep them warm and happy and roused quite a spirit of

enthusiasm. The program began with songs by different

groups. In the midst of it we found that the children were getting

cold, so we had an intermission during which they had some vigorous gymnastic

exercises. During the singing of the last song on the program Santa Claus

appeared, riding up to the front entrance in his sleigh and eight dashing

reindeer; only the sleigh was a gaily decorated ox-cart drawn by four yoke of oxen

which were driven by eight big boys all dressed up in white

sheets. Santa was well gotten up in red and white, and made a fine

appearance. The orphans very soon recognized him and were delighted

that the Hairig (Little father) [Rev. Henry H. Riggs] was giving them this

joy. He rode around the yard once or twice and then stopped beside the

tree where he had distributed to the various orphanages great bags bulging with

presents. There was an American in charge of each group, and we

opened the bags and distributed the contents to the children and their

Mairigs (Matrons). Each Mairig received soap, and each child nuts

and raisins done up in a square of unbleached muslin to be used later as a

handkerchief. We knew of nothing that we could give all around that

would be more appreciated than handkerchiefs, for there had been none given out

before. If a child was able to get hold of a little piece of cloth

to use, he was fortunate. And they were all delighted. We

were able to put into each package three pieces of American candy, a very

special treat. It was quite a job to prepare all these packages

beforehand, but when we all worked together, twelve or more of us, we could

fill about 1, 200 in an evening.

It

was a most inspiring sight to see all our orphans together and to see their

happy faces and hear their expressions of gratitude and pleasure. We

all love the little ones, and they love us. We often see a thousand

of them together, but not 2,500, as they are scattered in different towns, and

we have no building that would hold them all. We are very happy that

we could have the gathering that day, for ever since the weather has been very

bad, and snowy.

While

we were all at the celebration at the Hospital one of our nurses, Miss Stively

[Florence M. Stively], had a happy time with the children and the old ladies

who were not able to go down the hill. Later in the week I put on

the Santa costume and made the rounds, to the delight of the children in the

neighborhood. I was most touched when I visited the Scabies children

for they have so very little to brighten their lives. I had in the

pack on my back a few little dolls that I had left in the girl’s ward as

permanent equipment, and some pictures for the boys. What a joy

it is to be able to give joy especially to the little ones who have suffered so

much during their short lives as these little ones have done.”

We now add here

some additional perspective on both Harpoot and the Christmas celebration

planning and the actual celebration from letters written by Dr. Parmelee.

“Harpoot, Oct.

26, 1919

“Dear Ones, …we

are none too many for all the work there is to be done. We have more

orphans here, than any in any one center this side of the

Caucasus. And we cannot now give as much personal attention as is

being given in some of the units where they have proportionately more American

workers for their number of orphans. We are trying to examine the

orphans and get their eyes, teeth, skin lesions etc. attended to. We

try to do a lot of physical examinations on Saturdays – last time it was

more than a hundred. With four thousand in all, as we expect soon to

have, when we have taken in several hundred more in November, it seems like an

appalling job. This number includes those in Malatia, Arabkir (a few

hundred) , and what we call outside orphans – supported with their

relatives. So we here may not have all of the four thousand to

examine, but we shall have the large proportion of them. Miss

Stively [Florence M. Stively, R.N.] has been doing splendid work, getting after

the children’s teeth, eyes, intestinal parasites etc. Just now we

have the dentist of the A.C.R.N.E. here for a few weeks. He did not

seem anxious to work on the teeth of the orphans, but we did not believe in his

limiting his work to a handful of American workers, who are many of them going

home in the spring anyway, so we have produced the cases from day to day, and

then, the work Miss Stively had already accomplished with the bad gums also

encouraged him to fall to, somewhat.”

“Harpoot, Turkey,

Dec. 28, 1919

“Dear Friends,

At this season of

the year, our hearts turn very naturally to our dear friends in the home-land

– longing to see you all, and yet happy to be able to cheer up those who

in such great need and darkness. In America I should have been

tempted to spend a more selfish Christmas, while here I must take some of the

many opportunities to do for others.

Our celebration

is being spread over some days, even our own festivities, because of the

absence of some of our circle. We gave each other some remembrances

on Christmas morning, but are reserving our turkey dinner till we are all

together again. Then, as the Armenian New Year’s and Christmas

come later than ours, we are planning our entertainment for the

orphans about ten days from now, if we can catch some fine day. It

is to be in the hospital compound, this being the most central

location. We hope to have some other gifts for our sick children and

the hospital workers, but for the orphans in general, the gift will be a square

of unbleached muslin (to be used as a handkerchief later) with some raisins,

roasted peas (a special kind, which is liked very much), and three pieces of

American hard candy. We have begun preparing these, doing eight

hundred of them the other evening. There will have to be several

evenings more of work to get it all done!

With the many

nice cards given me by many friends, I was able to give fresh ones, not only to

native helpers, but also but also to the American personnel, and had pasted

ones with a Christmas verse written on each one, for the patients. I

also went to the Cripple Home and gave them cards and a little

treat. You see what service the cards give to the people whose lives

are so dreary. Every bit of brightness is appreciated.”…You would

see a great change in many of our orphans now, from last

summer. Their faces are fatter, freer from sores, and their clothes

are warm and neatly made. I love to see some of our little boys on

the street in their fine woolen suits. I hope many of you may have

the privilege of adopting a bright little boy or girl.”…We have had some snow

this month, but on the whole the winter is holding off very well. We

had lovely mild weather on into late November, so we must expect now to shiver

somewhat. And we have enough clothes, and some

heat! What of the people in rags who frequent our

clinics? It is no wonder that they camp on the porch and declare

that they are going to stay in the hospital, but we cannot shelter them

all. Lately we have been combatting a young typhus epidemic, but we

went at it so vigorously, that we hope it will go no farther. It is

a joy to treat typhus patients in clean hospital beds, compared to dark hovels

and piles of rags, as I was wont to visit them in 1915 to 1917.”

The following,

while written considerably later in the summer of 1920 is included since it

gives the names of a few of the orphanages that the orphans traveled from to

attend the Christmas celebrations in January of that year.

“Harpoot, Turkey,

August 25, 1920

“Dear Friends,

Yesterday I had a

sightseeing tour of some of our orphanages scattered about the plain…inspecting

gardens, house, and children – health, cleanliness etc. Morenik was the

first place we visited. Here we were greeted by the kiddies at the

edge of the village, dressed according to summer rule...in their unbleached

under-garments...we turned to Keserik where are stationed four orphanages this

summer. Three of them spent the winter [of 1919] out there, also, for

which I feel we should give great credit to the “mothers” and “sisters” of the

orphans.16

Here follow some

of Dr. Parmelee’s comments on Mairigs in one of her

letters.

“…tour to the

orphanage institutions. Some of the families of about a hundred orphans

each we find living in flat-roofed mud houses built for single families, either

in the town or in villages from three to ten miles out on the surrounding

plain. A hearty welcome is forthcoming from the hard-working

house-mothers or “Mairigs”, who are wonderfully brave to care for their many

children in such crowded quarters with less than minimum supplies and equipment

of all kinds. Perhaps the youngsters are seated on the earth floor,

eating their soup out of earthenware bowls. Or if our visit takes

place during school hours, the sleeping quarters of the orphanage would be

turned into a schoolroom by putting the bedding away in piles, and we would

find the pupils sitting on the floor in front of their teacher.”…“I should not

enjoy living in a wretched little village, either winter or summer. But

it relieves the housing problem considerably, and enables us to get the

benefit of some of the gardens now in our control. Here in one of

the orphanages we found some looms with unfinished mats on them. I

understand that this work is only hampered by the lack of rags from the

tailor-shop. I might explain that our school-teachers were asked to

spend about five weeks of their vacation in these orphanage schools. …Then

for our longest trip – to Hoolavank [Khoolehvank],

one of our monastery farms right out in the country. Theirs is

really close-to-nature life, and what an enthusiastic farmer is the husky

village woman at the head of the permanent orphanage. She and her

assistants and the whole group welcomed us cordially, fed us on delicious

melon, and begged us to stay longer. The children told us happily

that the chapel was being repaired − a relic of better days

for the Armenian community. We called the nurse’s helper (we have

stationed one in almost every orphanage) and gave her the suggestions and

help she needed, and then accepted the hospitality offered us,

glanced at some of the vines in the garden, and turned back to the rough

country road over which we had come. One other village and orphanage [not specified

regrettably] finished our day. My special joy was seeing old

friends. Among the children, there were many old patients, grown fat

and rosy now. Little Victor last year was suffering from marasmus

[severe malnutrition] and could not stand up on her weak legs, when we took her

under our care. Makrid had lung trouble and just escaped

having to go to the sanitarium – a sweet, helpful child she

is. I saw little Bedros who had a broken leg and meningitis, both at

the same time – his mischievous smile could not escape one’s

notice. Our cross-eyed pet, Marsoob, who was in the hospital for

spinal trouble, seemed as straight and strong as could be. To see a

few results of this sort, is certainly encouraging. It is due not

only to the hospital, but the food and clothing and better care of this whole

regime, brought about by the “Near East Relief” and its supporters!”

________________________________________

The following

account by Dr. Parmelee was written on the latter part of the day

after the Christmas celebrations were over.

“The Orphans’

Christmas Tree, Harpoot, Turkey, Jan. 8, 1920

“By nine o’clock

in the morning the first orphanage had arrived and was waiting patiently

outside the hospital gate. They had gotten up early in the morning,

in order to come their eight or ten miles from Hulavank, their village

orphanage. It was worth it, for could they not watch the

preparations going on in the yard? The boys had been out and swept,

and had then installed the wonderful tree, a combination of two small

ones. Then came the paper chains and strings of tinsel, and even

dyed spools, and American flags, and then to top it all, some wiring and

electric bulbs. Who would have dreamed to see an electric lighted tree

in this out-of-the- way place!

After a time, all

was ready and the posts put up, which indicated where each group was to be

stationed. There must be careful planning, for as someone expressed

it, the “world was to be our guests” on this eventful day. We

wondered whether the yard would be crowned with the 2500 children and adults

whom we were expecting. But, arranged in groups, as they were,

everything went off very quietly and in an orderly manner.

As the different

orphanages were marching in, those already there on the ground began counting

the number of their orphanage, like real football yells. Then came

the program, which consisted mostly of songs from different

groups. The children sang very well, marching up on the front porch

to performs and then, in some cases, joining in the clapping

afterwards! I might say that the weather man was anxious that we

give the youngsters a good time, and furnished a beautiful day, the sunshine

warm enough in the middle of the day to make an outdoor entertainment

possible. When the songs had been sung, a little gymnastics indulged

in, in order to get warm enough, and the kindergarten children had played their

snow-ball game, the whole gathering were asked to sing together. And

then - the gate opened to allow the queerest Santa Claus outfit that you could

ever imagine, to drive in. First, there came seven orphan boys

draped in white, leading four pair of oxen decorated with carpets, behind which

came the cart festooned with red calico and evergreens, and standing up in it was

the trimmest Santa Claus you ever saw, dressed in the regulation red suit and

white beard. The children, delighted, exclaimed that it was the

“Hairig” (Father), who had come to give them gifts. After driving

around the circle several times, Santa Claus stopped and began to distribute

the handkerchiefs containing raisins, a kind of roasted peas, and three pieces

of American candy. Each orphanage

had its bag containing the right number, and these bags had been stacked around

the foot of the tree. As each group had been assigned to an

American, it took but a few moments for the assistants of Santa Claus to get a

gift into the hands of each child. The mothers of the orphanages

received a cake of laundry soap and one of Ivory soap as their present. And

all too soon, the groups had to turn their faces homeward, many of them having

come down the hill, all of the three miles. Unfortunately they could

not stay until dark, to really enjoy the electric lights, but we here at the

hospital could! It was interesting to see the long lines of children

as they wended their way towards the foot of the hill. We were able

to furnish a little motor transportation to some of the feeble and little

ones. What a bit of enjoyment, compared to all that we have received

in our full lives, and yet, I suppose we cannot imagine how much real pleasure

came into the lives of our little ones, this Christmas. Let’s do it

again!”

(Parenthetically,

Dr. Parmelee had been present when Dr. Herbert Atkinson had died from typhus on

Christmas Day, December 25, 1915. Her memories of earlier

Christmases in Harpoot must indeed have been in the back of her mind.)

We present now a

few excerpts written by Dr. Parmelee on January 26, 1920 but first we present

the following excerpt from a letter written by one of the younger A.C.R.N.E.

workers at Harput (she was born in 1891), Frances MacDaniels.

A letter about

the Christmas Celebration from Mrs. Frances C. MacDaniels

The following

letter written by Mrs. Frances Cochran MacDaniels to her family back in

Cincinnati describes the Christmas celebrations as well and allows us to fill

in some more details. She and her husband (they married June 1916)

had left the United States on February 17, 1919 on the board the Leviathan,

the first major relief ship of the A.C.R.N.E. The MacDaniels and Dr.

Parmelee and others were on the Leviathan. They ended

up staying at Derindje on the Marmora coast. Derindje was a deep

water port facility built by the Germans complete with a spur of the railroad. They

were obliged to stay there for a long

time doing duty on all sorts of essential things related to the relief and

reconstruction efforts. The MacDaniels and Dr. Parmelee et al. were

part of the last relief group to leave Derindje. They were

assigned to Harput in the interior but did not leave to go out until in

mid-May. Laurence H. MacDaniels, who had earned a Ph.D. at Cornell

University in the Field of Botany and was later to have a very distinguished

career in applied botanical science at Cornell, had the job of being Assistant

Director at Harput and was in charge of the business end of the relief work,

the housing etc. And be it said that the et cetera was

very extensive and crucial. Mrs. MacDaniels, who had had some experience

in orphanage and poor house work in Cincinnati served as book keeper (assisting

her husband), housekeeper for the portion of the Relief Unit who resided on the

hill etc. Again the et cetera entailed many tasks

and chores. Both did their undergraduate studies at Oberlin College

and it is there that their papers concerning their service to A.C.R.N.E. are

deposited in the Archives (http://www.oberlin.edu/archive/NearEast.html)

“January 11, 1920

[a Sunday]

“Dear

Folks:- I wish you could have seen our Santa Claus and his

reindeer! We had the Christmas celebration for the children last

Thursday [January 8]. It was a bright day, no snow for a couple of

weeks, so the ground was dry. We had all our 2800 kids come to the

hospital yard. The performance was to come at two, but in the middle

of the morning they began to arrive. As we rode down the hill after

lunch we passed orphanage after orphanage, rather suggestive of the

deportations. They each had a place in the yard and an

American to welcome and stay with them. We had a Juniper

tree made of several put together, decorated with dyed spools, the

ordinary chains, and little baskets and lanterns made of canned food labels,

together with some real trimmings left by the missionaries. They had

Christmas songs by the various orphanages, and a snowball fight by the

kindergarten kids. To warm them up before the feature

of the afternoon Mr. Means [Gardiner C. Means] got up on the hospital porch and

led off in some exercises; these made a great hit, literally as well as

figuratively, for they didn’t spread out enough to miss each other’s noses.

Just as they got

settled down again the gates swung open and Santa (Mr. Riggs in a regular Santa

costume) dashed(?) in in a two wheeled ox cart drawn by four yoke of

oxen. The cart was gaily decorated with bright red cloth and

evergreens, the oxen each wearing red and white striped kilim. The

boys driving the oxen were swathed in sheets. They circled around

the drive a couple of times amidst the cheers of the children and stopped

beside the tree. Santa, after a speech, got out and pulled out a

large bag for each orphanage, from under the tree. Each bag

contained for each child an unbleached muslin handkerchief full of leblebs,17 raisins

and three pieces of candy. For each mairig [little mother] and

quirig [little sister] two cakes of soap. It was fun to watch the

different children. Some tucked theirs away untouched, others opened

and dove in, going away with only the empty handkerchief. They

searched out the candies, and some started swapping red for green, etc., like

regular children. I suppose some swapped licks off of them too.

We certainly

enjoyed it all even more than the children. We had lots of fun

filling these handkerchiefs too. Mac [her husband Laurence] was away

so not only missed seeing it, but could not get a good picture and we hope to

find some good ones among them, tho with all these others photography is a matter

of luck.18

We had our

Christmas dinner on New Year’s day. Thirty one at the

table. The two girls who were hurt coming in, one with her head

bound up, the other with her arm in a splint, were there, two men who were

bringing them in and two who got snowed in here, Schwester Merena,18 the

only relic of the German mission personal and all. The dinner was a

huge success.”…

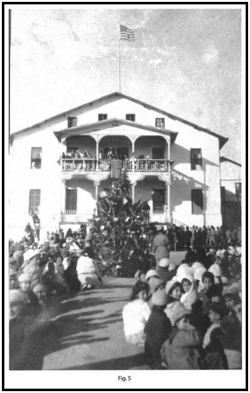

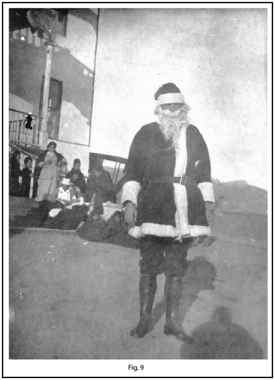

The following

several photos (Figs. 5 through Fig. 9) show some highlights of the

celebrations. We thank Oberlin College Archives for permission to

present these.

Fig.

5. Armenian orphans in the courtyard at what was earlier called the

Annie Tracy Riggs Hospital compound. (It came to be called Near East

Relief American Hospital, Kharput after the A.C.R.N.E. relief efforts took

hold). The Christmas tree, complete with electric lights, is

directly in front of the Hospital. Note the American

flag. From the MacDaniels Near East Relief Album,

Oberlin College Archives.

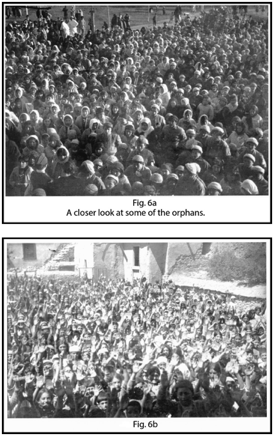

Figs.6a

and 6b. Closer views of the orphans in attendance at the Christmas

celebration.

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8. Santa Claus in his

sleigh (ox cart) drawn by ‘stand-ins’ a.k.a. oxen for reindeer who had

apparently been previously engaged elsewhere. The drivers are older

Armenian lads clad in white sheets. Oberlin College Archives.

Fig.

9. Rev. Henry H. Riggs in his Santa Claus costume. The

porch of the Hospital may be seen in the background. Note some of

the orphans on the ground wrapped in blankets (see letter describing this

above). From the MacDaniels Near East Relief Album,

Oberlin College Archives.

Fig. 10a and Fig.

10b. Enlargement of Dr. Riggs from the photograph of him in costume

(Fig. 9) and juxtaposed with an image from a photograph taken slightly later in

America. Santa was clearly a bit thinner in Harpoot.

Letter

from Dr. Parmelee on More Christmas Celebrations

On January 26,

1920 she wrote of her additional Christmas activities.

“Dear Folks, On

January 13th I attended the Christmas tree in Miss [Karen

Marie] Petersen’s [Danish] orphanage where Miss [Jean M.]Turnbull is at present

rooming; on the 14th one at the girl’s boarding

school. On the 17th we had our celebration here at

the hospital, inviting the children from the Cripple Home. The tree

was set up in the hall just outside my door, and we tried to get the place

warmed a bit with mangals [braziers, the finest of which were

made of brass]. The electric lights gave a swell appearance to the

tree. We had some Christmas music. Dr. Ward [Mark H.

Ward, M.D.] dressed up as Santa Claus and distributed gifts. We had

oranges for refreshment, cards, and a gift for more than sixty-five workers

connected with the medical department – not including American personnel

of course. On Armenian Christmas, the 19th, I did some

calling, and attended one more orphanage entertainment. Those who

know the language, have to go it strong.”

POSTSCRIPT

We

have gone the extra mile so to speak to present the “Christmas for the Orphans”

in a context that hopefully makes clear the very bittersweet nature of the day

and indeed the times for Armenians in general. It was of some

interest to us that we could find no mention anywhere of Gaghant Baba (Armenian

for Father Christmas) or the common Kharpertsi greetings of the

season – Shunahvor Nor Daree yev Paree Gaghant, signifying “Happy New

Year and Merry Christmas.”

The

natural question that arises after having read all these accounts is “What

happened to them –the orphans, the adults?” Some readers may

be able, we hope, to delve in the ‘family archival memory bank’ and retrieve a

few answers. The fact is, however, that things got so bad in the

early Kemalist period that it became clear that any orphans in the care of Near

East Relief would best be brought out of Turkey. This is a story

unto itself of course, and a fair amount has been written about this.19

It

is the story of the adults that is far more varied and many blanks remain to be

fitted into the whole. Hopefully some Groong readers will consider

this all food for thought.

ENDNOTES

1. 1. We have made no attempt

to reference this paper every step of the way but we have felt obliged to

include some citations to the literature. These are provided in

these fairly extensive Endnotes. We have also included two

Appendices because we feel strongly that certain information needs to be

included. Their substantial length emphasizes that we know some of

the younger generation have an incomplete understanding of the region and the

times. This is, of course, understandable since with the passage of

time we all become more remote from what we were told while growing up about

the erkir (or ergir – “the Land,” the “Old

Country”) in those days of long ago. Our first Appendix attempts to

deal in some detail with the dating of the celebration of Christmas especially

by the Armenians. Appendix 2 is concerned with the place names

Kharpert and Mezreh or Mezereh. Needless to say, placing these at

the very end indicates that one need not be distracted in his or her reading of

the paper by referring to any of this. They have only been added to

achieve some measure of completeness.

2. Harpoot and its

pronunciation. Harpoot is but one spelling in romanized

transliteration of the Armenian Kharpert. Harput is

generally retained in the Turkish spelling. For details on Armenian

Kharpert in English one can refer to Richard G. Hovannisian, ed. Armenian

Tsopk/Kharpert, (Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers,

2002). For a general but good account of the events at Harpoot

during and immediately after the Hamidian massacres and the relief work with

orphans of that period etc. one can refer to William Ellsworth Strong’s “The

Story of the American Board; an Account of the First Hundred Years of the

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions” (Boston, New York, The

Pilgrim Press; American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1910)

– for a digitized version refer to https://archive.org/details/storyofamericanb1910stro. A

more modern perspective on the broad range of activities undertaken by the

American missionaries is provided by Barbara J. Merguerian in her “Missions in

Eden: Shaping an Educational and Social Program for the Armenians of Eastern

Turkey” in New Faith in Ancient Lands. Western Missions in the Middle East in

the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, ed. Heleen Murre-van den Berg

(Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2007). Reference should also be made to

Jonathan Conant Page’s “Ringing the Gotchnag: Two American Missionary Families in

Turkey, 1855-1922” (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society,

2009). It is a very readable, yet scholarly account of the

long-serving missionary families of Wheeler, Barnum and Allen and their work at

Harpoot.

2. 3. See for

example The Missionary Herald vol. 72 January (1876) pg. 5.

3. Herman Norton

Barnum, D.D., was born in rural upstate New York near Auburn on December 5,

1826. He graduated from Amherst College, Class of 1852 and from

Andover Theological Seminary in 1855. In July 1860 he married Mary

E. Goodell, daughter of Rev. William Goodell who served as a missionary in

Constantinople for a good many years. Rev. Barnum joined the Harpoot

Station of the American Board in 1857, and his wife came one year

later. The Station had been occupied since 1855 and permanently

since 1860. The Barnums were one of the three families (Wheeler,

Allen, Barnum) who continued to serve in Harpoot until 1896. Rev.

Barnum died in Harpoot 19 May 1910 and his wife Mary died nearly exactly 5 years

later also in Harpoot. They had nine children, six of whom died in

childhood. All were buried in Harpoot.

4. 4. Winston S.

Churchill (1929 and other editions) “The World Crisis: the Aftermath (C.

Scribner’s Sons, New York pg. 405.

5. 5. See pg. 79 of

“The Slaughterhouse Province. An American Diplomat’s Report on the

Armenian Genocide, 1915-1917” (ed. By Susan K. Blair, Aristide D. Caratzas,

Publisher, New Rochelle, New York, 1989). While spelling of these

Village names is by no means uniform, it will be possible in many cases to

locate them on the map in Figure 1.

7. 6. See

for instance Taylor, E.L. and A.D. Krikorian (2011) “Educating

the Public and mustering support for the ratification of the Genocide

Convention: Transcript of United Nations Casebook Chapter XXI: Genocide, a

13 February 1949 Television Broadcast Hosted by Quincy Howe with Raphael

Lemkin, Emanuel Celler and Ivan Kerno.” War Crimes,

Genocide & Crimes against Humanity Vol. 5: 91‐124.

8. 7. Susan

K. Blair’s edited version of Consul Leslie A. Davis’ final report that she

framed in the context of the title “Slaughterhouse Province” provides much

evidence that supports this viewpoint. Vahakn Dadrian has drawn

attention with reference to the Military Tribunal Trials to the key indictment

of Dr. Behaettin Sakir, one of the most influential and ruthless of the

Ittihadist leaders. A telegram was sent to his subordinate in

Mamuret ul Aziz (Harput) Vilayet on 21 June 1915 demanding to know whether the

Armenian leaders there, referred to cryptically as “harmful people” were being

promptly liquidated or merely ‘deported’ – see pg. 84 of V. Dadrian

(1993) “The secret Young-Turk Ittihadist Conference and the decision for the

World War I genocide of the Armenians” Holocaust and Genocide Studies vol.

7, no. 2 pgs. 173-204.) It is noteworthy that Dr. Mark H. Ward who

served at Harpoot describes in his “The Deportations of Asia Minor, 1921-1922”

(London, 1922 published by the Anglo-Hellenic League and the British Armenia

Committee) wherein he speaks mostly of the deportation of the Greeks (and any

residual Armenians) from the Pontus area mentions that about 5,000 out of some

30,000 deportees “escaped from the convoys.” One doesn’t know what

eventually happened to these escapees but the death toll out of the whole was

huge. What had happened to the Armenians was now being carried out

on the Greeks. His writings give a fairly good idea of numbers involved. Parenthetically,

this state of affairs provides one of the several reasons we believe that there

are many more descendants of Kharpertsis in the Diaspora. Far fewer

Diasporan Armenian descendants are to be encountered whose roots lie in other

places of Turkish Armenia like Sassoon, Bitlis, Moosh, Erzerum, Angora,

Shabin-KaraHissar, Kars etc. Attempts at the extermination of the

Armenians through genocide would appear to have been somewhat more fanatical

and efficient, relatively speaking of course, in these areas. This

perverted diligence due to regional peculiarities or even specific Turkish

regional administrators perhaps accounts for the fact that there seem to have

been fewer opportunities for survival of Armenians in/from these places.

9. 8. Another

perspective that might be mentioned for a fuller equation is that in a

male-dominated society such as that of Ottoman Turkey the act of ‘decapitating’

the nation (literally and figuratively) by getting rid of men and youths, and

uprooting the remnants by deportation (predominantly women and children) the

task of destruction was for all practical purposes complete. By

analogy, ripping a plant out of the soil and allowing it to wither and die, was

an adequate solution to any Armenian problem.

10. 9. Those

relatively few Armenians who were able to be taken into Turkish homes as

servants, usually in absolute slavery, could keep relatively low profiles and

ended up remaining and not deported. Some Armenians made the painful

decision to leave their children with Turkish neighbors who were willing to

take them (some Armenians, and even some Turks, actually thought the Armenians

would be ‘deported’ temporarily and would one day return – others left

children knowing full well that they themselves would probably end up dead but

that there was at least a possibility that their children might survive in a

Turkish household – probably not as Armenians but absorbed as Turks, but

at least still alive! Some women married Muslims to save themselves

and their children, they themselves in the process becoming Turkified (turkatsad

or turkuvadz in the colloquial Kharpetsi Armenian dialect of the

period). Others were taken in, having been stolen from their family

unit – sometimes literally yanked away from a hysterical mother, or

kidnapped by stealth, sold by the kidnapper(s), and used once they were

‘deposited’ and ‘settled’, perhaps as concubines (a word we dislike immensely

but admit that it reflects their role maybe as a secondary or tertiary ‘wife’

etc.) Some Armenians were allowed to stay because a particularly

influential Turkish or Kurdish Agha needed the wheat in his fields or whatever

to be harvested. (Wheat fields generally went to ruin since the

wheat harvests were not ‘in’ when the villages of the Kharpert Plain were

forcibly emptied.) Again, this kind of respite was usually temporary

but could offer subsequent opportunities for escaping, fleeing and

hiding. The mentally handicapped, or those feigning insanity or who

were even really insane (some were driven mad by the events of the period

– stories heard from survivors) were not ‘deported’ because they were

feared by Muslims and tended to be avoided at any cost. And,

certainly there were other categories that we have not mentioned. We

will not make any serious attempt here to analyze the specifics of any seeming

altruism in the context of the Armenian genocide on the part of those Turks and

Kurds who were willing to take the risk to shelter Armenians or help them

escape. Such activity was supposedly against the law but the law was

repeatedly ignored because the ruling was very arbitrarily applied and enforced

by local authorities. Bribery and extortion were

rampant. More than a little money passed hands – the

proverbial greedy ‘blind eye and deaf ear’ for financial or material gain

reigned supreme. Our deep familiarity with the stories of Kharpert

survivors has convinced us that little was done to help most adults (all women)

at least until caravans reached northern Syria

[Suriya]. Still further south, Orthodox Jews sometimes engaged

Armenian women to light their Sabbath fires and thus enabled them to earn

a para or two. Children were another

matter. One admittedly Turcophobe writer put it this way:- Turks

sought to refresh their ‘worn-out blood’ – for “the Turks are a worn-out

and decadent race – by infusing the blood of a younger and more vigorous

nation by this hideous policy.” We have no compunction in throwing

in for some additional measure of completeness that one can find nowadays more

than a few attempts to soften, even rehabilitate, the image of the ‘terrible

Turk’ by arguing that there indeed were many “righteous” Turks who ‘saved’

Armenians. (Note the use of the equivalent expression “righteous”

adopted by the Government of Israel to describe those gentiles who acted to

save Jews in the Nazi period.)

Truly unselfish

acts of kindness on the part of Turks were in our opinion very rare

indeed. The subject of Turkish altruism has been brought up from

time to time even by writers of Armenian heritage, but by and large we remain

unconvinced based on what we know and have heard from those who were ‘taken in’

by Turks. “Turkihn askuh korna” [“may the eyes of the Turk be

blinded”—note the use of the word korna for blinded is

Turkish] was quite often heard by one of us (ADK) growing up amongst genocide

survivors from the villages. This curse and malediction stands out

in stark contrast to the well-wisher who sought to offer good wishes or

congratulations with “Ashkid luys” or “light to thine eyes.” Kurds

and Arabs, on the other hand, seem to have been motivated by more humanitarian

reasons. Robert Fisk, journalist for The Independent (London)

and an author who we generally admire and respect, has on occasion attempted to

draw attention to “righteous” Turks and he has suggested that this could serve

as a potential avenue or gesture to reach out for reconciliation

(see his “The Great War for Civilization” (2005) Chapter 10 “The First

Holocaust” pgs. 316-350.) But, we will soon gain some insights in

this orphan Christmas presentation gained on the spot on this topic as we

proceed in this paper since it will be obvious that many Turks seem to have

heard of “Cast your bread upon the water for after many days you will find it

again”, Ecclesiastes 11: 1-6.) [We have heard the same framed

sarcastically as “Cast your bread on the water when the tide is coming in!” It

won’t do you any harm to do some good – quite the opposite!]

11. 10. Ruth Azniv Parmelee is a person who many have heard of in

reference to Armenians – see for instance our contribution with some

photographs at http://groong.usc.edu/orig/ak-20110627.html − and later

in connection with the Greeks. She was no stranger to relief work

for Armenians. Her parents offered assistance to Armenians in

Trebizond after the Hamidian massacres when she and her slightly older brother

Julius were children of about 12 and 10 years old respectively – but old

enough to know what had gone on. Considerably later, after she had

gone to America for her education and her eventual medical training and earning

her M.D., she returned with her widowed mother to Harpoot in 1914 and began to

carry out medical, especially obstetric and pediatric, work. After

her return to America in 1917, having left Harpoot with Consul Davis and other

missionaries on May 17, she wrote at the request of Rev. Dr. James L. Barton,

Foreign Secretary of the American Board for Foreign Missions in Boston, a

statement under the telling rubric of “massacre conditions at Harpoot,

Turkey.” Highlighted in her deposition was her “Visit to the Exile

Camp in Mezereh.” In reminiscing a number of years later about her

work in an article entitled “Twenty Years in the Near East” [Women in

Medicine 51, January, 1936 pgs. 20-23] she said of the summer of 1915